Africa

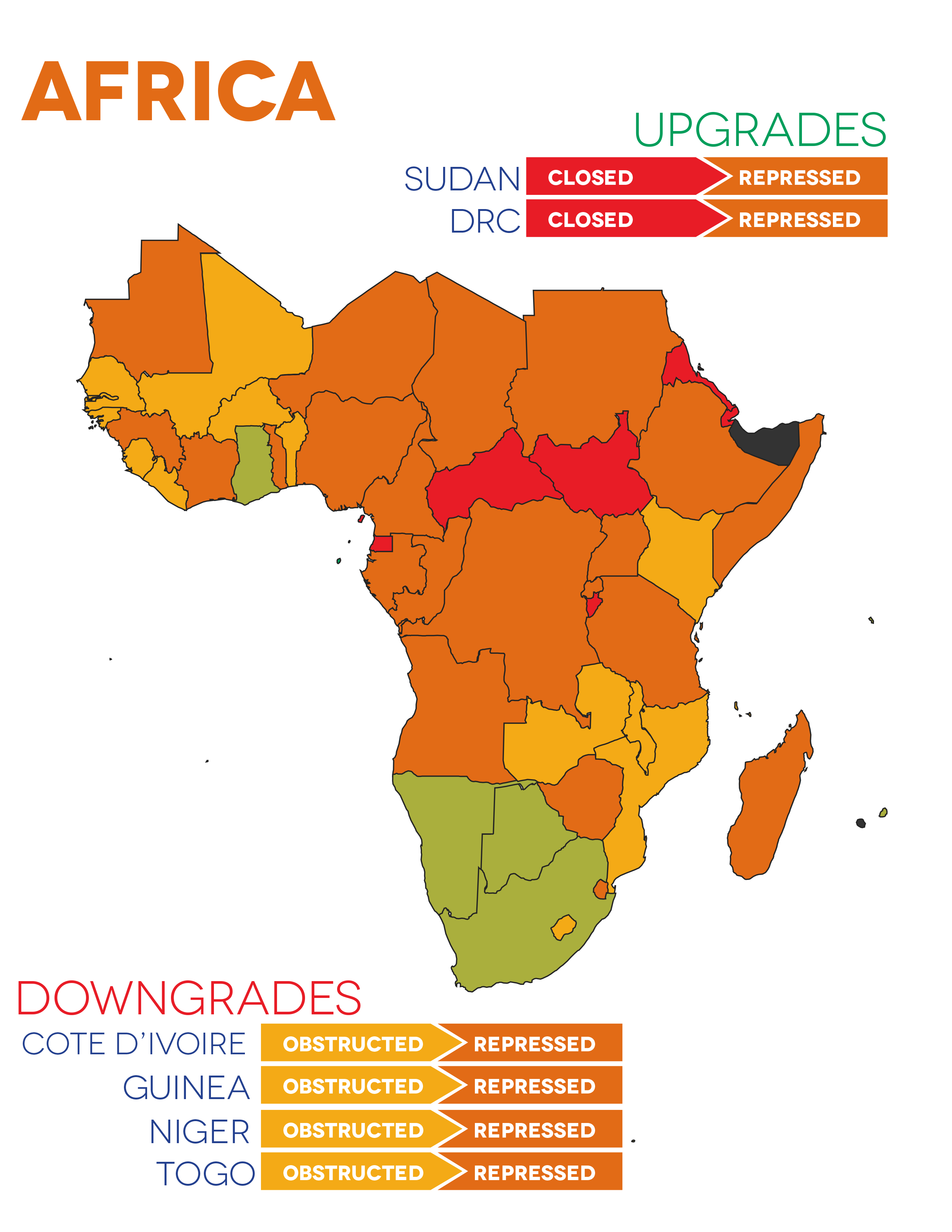

Of Africa’s 49 countries, six are rated as closed, 21 as repressed and 14 as obstructed. Civic space is open in the island states of Cabo Verde and São Tomé and Principe and narrowed in six countries. Since the previous update, civic space ratings have deteriorated in Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Niger and Togo and improved in the DRC and Sudan.

Ratings Overview

Civic space in Central Africa remains affected by armed conflict, weak rule of law, impunity and entrenched authoritarian governments. In Cameroon, where conflict in the Anglophone regions continues unabated with serious human rights abuses perpetrated both by armed separatist groups and the military, civic freedoms remain severely restricted. 2020 saw for example the ordering of closure of bank accounts of a COVID-19 solidarity fund initiative set up by opposition leader Maurice Kamto, the arrest of some of its volunteers who were handing out masks and sanitisers and accusations by the Minister of Territorial Administration that some CSOs are ‘destabilising the country’. An improved rating in the DRC reflects initial steps under the administration of President Tshisekedi to open democratic space, although much more must be done to fulfil the president’s promises made in his inauguration speech in January 2019 to respect the fundamental freedom of people and media freedom.

As the decline in ratings for Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Niger and Togo indicates, civic space continues to decline in West Africa, where several countries held disputed elections. Pro-democracy and anti-corruption groups and activists have increasingly been targeted and protests have been met with excessive force. In Benin, the 2018 Digital Code has increasingly been used against people expressing critical views. Following mass anti-government protests in June and July 2020, in which at least 11 protesters were killed, Mali’s military toppled the government in a coup. A transitional government, appointed in October 2020, will rule for 18 months until elections take place in 2022. Attacks and threats against journalists have become commonplace in Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone.

In Southern Africa, protests – on issues of labour rights, service delivery and gender-based violence – were dispersed by force, including in Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa. In Eswatini (Swaziland) and Zambia, the freedom of expression continues to face severe constraints, with the authorities targeting media outlets with suspension and their employees with arrest. Protesters advocating for good governance and democracy in Zambia were intimidated by the authorities, while those in Eswatini were harassed with house raids. In Zimbabwe, amid a declining economy and regular workers’ strikes and boycotts, the government has continued to restrict the freedoms of association and peaceful assembly.

In the East and Horn of Africa, the authorities in Tanzania continued to crack down on civic space ahead of the October 2020 elections, with harassment, intimidation, arbitrary arrests and judicial prosecution of political opposition, human rights defenders and journalists. Media coverage on COVID-19 has been silenced and it has become increasingly difficult for human rights organisations to operate. Positive political changes in Ethiopia in 2018 have been undermined by a renewed clampdown on independent media and opposition and a violent response to protests amid worsening intercommunal and ethnic tensions. The improvement of Sudan’s civic space rating reflects an opening up of space for activists and journalists following the formation of a transitional government and initial reforms, although much work, including the repeal of restrictive laws, still needs to be done. In a negative development, individuals and CSOs in three countries will no longer be allowed to appeal directly to the African Court on Human and People’s Rights: Tanzania withdrew this vital accountability route in December 2019, followed by Benin and Côte d’Ivoire in April 2020.

In a negative development, individuals and CSOs in three countries will no longer be allowed to appeal directly to the African Court on Human and People’s Rights: Tanzania withdrew this vital accountability route in December 2019, followed by Benin and Côte d’Ivoire in April 2020.

Civic Space Restrictions

In Africa, the most common civic space violations registered by the CIVICUS Monitor in the reporting period were the detention of journalists, followed by protest disruption, censorship, intimidation and the detention of protestors.

Detention of journalists

The detention of journalists has become more prominent in Africa, mentioned in almost half of CIVICUS Monitor updates during this period, in 28 different countries.

In Somalia and South Sudan, journalists are frequently subject to arbitrary arrests for reports that are critical of authorities. In Cameroon, one of the top jailers of journalists on the continent, the military admitted after 10 months in June 2020 that journalist Samuel Abuwe Ajieka, also known as Samuel Wazizi, had died on 17 August 2019, shortly after his arrest. In Burundi, four journalists of the independent newspaper Iwacu – Egide Harerimana, Christine Kamikazi, Térence Mpozenzi and Agnès Ndirubusa – were convicted in January 2020 on charges of attempting to threaten to destabilise the internal security of the state, and sentenced to two and a half years in prison, along with a fine. The four were arrested in October 2019 while reporting on unrest that erupted after armed people crossed into Burundi from the DRC and clashed with another armed group.

Despite President Tshisekedi’s promise to turn the media into a ‘real fourth estate’, several journalists were detained for criminal defamation or insulting the authorities. Prior to the decriminalisation of libel and sedition in Sierra Leone in July 2020, Sylvia Blyden, publisher of the Awareness Times newspaper, was charged on 22 May 2020 with sedition, defamation and perversion of justice for a Facebook post, spending 50 days in prison before being released on bail.

Journalists have also been detained while covering protests or reporting on sensitive issues such as corruption. In Benin, Ignace Sossou, investigative reporter and editor for the online news outlet Benin Web TV, was sentenced on 24 December 2020 to 18 months in prison, later reduced, for ‘harassment by means of electronic communication’ after having quoted the public prosecutor on Twitter. In Zimbabwe, journalist Hopewell Chin’ono was arrested on 20 July 2020 and charged with incitement to participate in public violence for having exposed corruption in the procurement of COVID-19 medical supplies. In Ethiopia, journalist Belay Menaye, news anchor Mulugeta Anberbir and camera operator Misganaw Kefelgn were arrested in August 2020 and rearrested in September 2020 on accusations of incitement to violence for their reporting on the protests and unrest that followed the killing of Oromo singer and activist Hachalu Hundessa on 29 June 2020. In Djibouti in June and July 2020, several journalists were arrested while covering protests, with others being forced into hiding, following the arrest of a military officer who released a video alleging corruption among high-level military officers and clan-based discrimination within the military. At least six journalists were detained while covering protests, organised to demand the holding of municipal elections and improved living conditions, on 24 October 2020 in Angola. Over 100 people were detained that day, while police officers used excessive force against protesters.

Foreign correspondents have also been targeted. In Guinea, Thomas Dietrich, Le Média’s foreign correspondent, was assaulted and threatened by security forces after they noticed him filming them beating a protester. He was briefly detained and then deported to France with his accreditation withdrawn.

Journalists in several countries were also detained and arrested for reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic or for violating lockdown regulations, including in Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda and Somalia.

Protest disruption

Protest disruption was mentioned in 40 CIVICUS Monitor reports, covering 21 countries. The detention of protesters was reported in 33.3 per cent of updates, and the excessive use of force in 30.3 per cent. Protesters were killed during protests in the past year in several countries, including Côte d’Ivoire, DRC, Ethiopia, Guinea, Kenya, Nigeria and Mali.

Anti-corruption protests were dispersed by police in Niger in March 2020. Eight civil society leaders were arrested in relation to the protest. In Djibouti, where protests are rare due to the repressive environment, the protests that erupted in June and July 2020 were met with excessive police force. In Liberia, a protest against the dire state of the economy and government mismanagement of public funds on 6 January 2020 was dispersed by police officers using teargas and water cannon, injuring dozens of people. Following disputed legislative elections, mass anti-government protests broke out in Mali in June and July 2020. At least 11 protesters were killed in protests organised by the Mouvement du 5 juin – Rassemblement pour le Mali (5 June Movement - Rally for Mali) coalition between 10 and 12 July 2020. Underlying grievances of protesters included the failure of the government to respond to insecurity and stop violence, corruption and dire economic conditions. Zimbabwe’s police dispersed a protest on 31 July 2020 against government corruption and the country’s economic decline, arresting at least 20 protesters.

Service delivery, labour rights and student protests were also broken up in several countries. In Senegal, nine activists of the Noo Lank (We Refuse) movement were arrested during a November 2019 protest against an increase in electricity prices. These arrests prompted fresh civil society protests in December 2019 and January 2020, which were mostly banned by the local authorities, and some of them were dispersed. One person was killed and dozens injured in Kenya during protests in the Kasarani district of Nairobi against the poor state of the main road. In Benin, one student was killed on 24 March 2020 in clashes with police officers at the University of Abomey-Calavi. Students protested after three students were arrested for protest actions to demand the suspension of classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Eswatini, when thousands of civil servants gathered on 25 September 2020 to demand higher salaries, police used stun grenades, water cannon and teargas to disperse protesters. In Mali, a protest by teachers’ unions to demand higher wages in March 2020 was dispersed.

Protests against increasing insecurity took place and were dispersed in Burkina Faso. In eastern DRC, at least 10 protesters were killed in protests against violence against civilians by rebel militia, denouncing the failure of the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO), the UN peacekeeping mission, to protect civilians.

In the Gambia, protests organised in January 2020 by the Three Years Jotna (three years enough) movement to demand that President Adama Barrow step down after a transitional three-year period, as he promised in his election campaign, were met with force. At least 137 protesters were arrested, dozens were injured, two radio stations were suspended and the movement banned. In Nigeria, the #EndSARS youth-led protests against police brutality across the country were met with excessive violence, with at least 12 people killed at the Lekki toll gate in Lagos on 20 October 2020.

In Liberia, Namibia and South Africa, protests against gender-based violence, including high rates of sexual violence and femicide, were dispersed and disrupted by police officers. Ghanaian police dispersed a Black Lives Matter protest in Accra and detained and charged the organiser, Ernesto Yeboah of the Economic Freedom League.

Protests in relation to COVID-19, such as protests against curfews, the closure of markets, delays in the delivery of food parcels during lockdowns and the placement of COVID-19 testing centres, took place in several countries, including Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Senegal, South Africa and Uganda. Some of those protests were dispersed or turned violent.

Censorship

As in previous years, censorship was reported as a major violation in the Africa region, mentioned in 39 updates in 22 countries.

The shutdown of internet access or access to social media has become a widespread tactic used by the authorities to quell protests, particularly ahead of and during elections. Known digital rights violator Chad again blocked access to social media in July 2020 as a ‘temporary measure’ to prevent ‘the spread of messages of incitement to hatred and division’ after a video was shared of an altercation between a military officer and a group of mechanics, one of whom was shot dead. Another regular violator, Ethiopia, shut down the internet, affecting most parts of the country, from 29 June to 16 July 2020 as protests erupted over the killing of Hachalu Hundessa. In Mali, access to social media was partially disrupted during the mass anti-government protests that started on 10 July 2020. In Somalia, internet connectivity was cut following the impeachment of Somalia’s Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khaire after a vote of no confidence. Election-related shutdowns or disruptions occurred in Burundi and Guinea.

National media regulators have, as in previous years, suspended media outlets and journalists for their reporting. Tanzania’s Communication Regulatory Authority continued to suspend and fine media outlets; the Mwananchi daily newspaper’s online content licence was suspended, including for its COVID-19 coverage. The national media regulator in Gabon ordered, in January 2020, the confiscation of 7,000 copies of the Moutouki weekly over an article claiming that President Ali Bongo’s son, Noureddin Bongo Valentin, was accused by civil society groups of corruption, misuse of public funds and money laundering. In Rwanda, censorship of media and self-censorship remain commonplace with pro-government views dominating domestic media and the increasing blocking of media sites from abroad. In Somaliland, on 18 November 2019 the Ministry of Information suspended Horn Cable TV while security agents detained its chief editor, Abdiqaadir Saleban Aseyr. In Togo, three media outlets – L’Alternative, Fraternité and Liberté – were suspended by the media regulator in March and April 2020; Fraternité was suspended for criticising the suspension of the other two outlets. In June 2020, provincial authorities in Mongala province, DRC, ordered the dismissal of six journalists and the suspension of several others, in addition to the suspension of several programmes, ‘until further notice’.

Some newly adopted laws or draft laws curb the freedom of expression or attempt to increase censorship or self-censorship. Civil society in Nigeria has been campaigning and mobilising against the adoption of the 2019 Protection from Internet Falsehood and Manipulation and Other Related Offences Bill and the Hate Speech Bill. The first bill would make statements on social media that may ‘diminish public confidence’ in the government or compromise national security punishable by a three-year prison sentence and fine and would allow the authorities to order a shutdown of internet access and social media. A new amendment to Somalia’s Media Law further restricts the freedom of expression: confidentiality of sources is not protected and journalists are required to accredit and register on a government database. The law allows for fines for journalists, with no maximum limit on the size of the fine. In Niger, a new law adopted in July 2020 authorises the interception of phone communications in the context of the ‘fight against terrorism and transnational crime’.

Censorship also occurred in the form of the intimidation and silencing of critics, including academics. In South Sudan, Taban Lo Liyong, a renowned University of Juba academic, was suspended over an opinion piece criticising the government. University students and staff in South Sudan require permission from the National Security Service (NSS) for planned activities and undercover NSS agents operate on campuses. In Tanzania and Uganda, comedians and musicians came under fire for criticising politicians and governance structures. In Niger, at least three people, including civil society personnel, were arrested and charged under the 2019 Law on Cybercrime for criticising the government’s COVID-19 response, including through private messages on WhatsApp.

Country Case Studies

Hope in Malawi after sustained protests

Mass protests broke out against the results of Malawi’s presidential, legislative and local elections, held on 21 May 2019. Peter Mutharika of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) claimed to have won, but the elections were disputed and marred by allegations of fraud. Protests, initially calling for the resignation of the Malawi Electoral Commission but later encompassing wider grievances, were sustained. The authorities, and particularly police officers, responded to the protests with violence, including sexual violence against women, and human rights defenders and protest leaders were threatened. After the Constitutional Court nullified the election results in March 2020, the authorities further cracked down on activists and dissenting voices as fresh elections approached. Human rights defenders and protest leaders Timothy Mtambo, Reverend McDonald Sembereka and Gift Trapence were arrested in March 2020, while members of the judiciary were persecuted. Despite these challenges, the rerun of the elections on 27 June 2020 saw a change in power as opposition leader Lazarus Chakwera won a majority of votes.

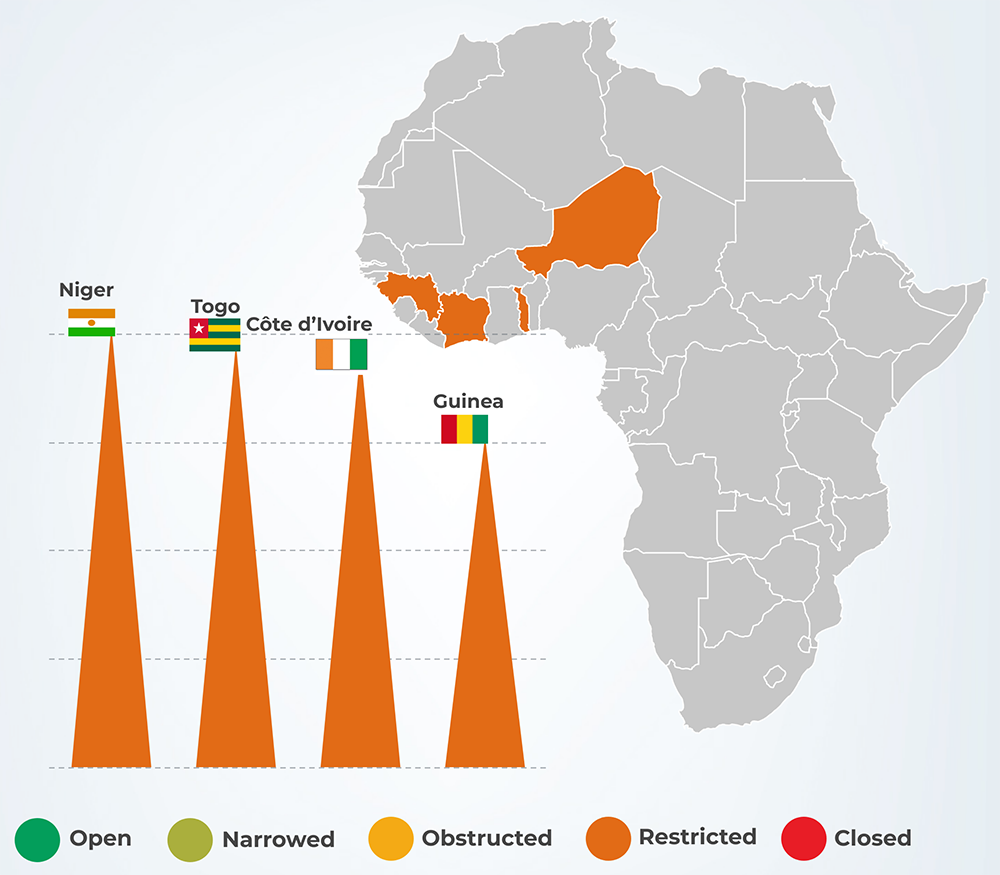

Countries of concern: civic freedoms in the balance in West Africa

The downgrading of four West Africa countries – Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Niger and Togo – just a year after Nigeria’s rating was changed to repressed and two years after Senegal’s rating was downgraded to obstructed, indicates a downward trend in the region. In Côte d’Ivoire, protests and violence broke out in August 2020 following President Alassane Ouattara’s announcement that he would run for a third term in the 31 October 2020 election. Dozens were killed in unrest and protests that followed the announcement. The authorities in Côte d’Ivoire have in recent years adopted and used repressive provisions limiting the freedom of expression, targeted at activists, including online activists, and journalists. In Guinea, a country that featured on the CIVICUS Monitor’s Watch List of countries where there is a serious and rapid decline in respect for civic space, mass protests mobilised from October 2019 against President Alpha Condé’s decision to change the constitution to allow him to run for a third term in October 2020. Protesters were met with excessive violence, including live ammunition, with security forces killing dozens of people and arresting many more. Pro-democracy activists and human rights defenders were targeted and subjected to arbitrary arrests, judicial harassment and prosecution.

Civil society protests are almost systematically banned in Niger, which was placed on the CIVICUS Monitor Watch List in June 2020. 2020 was marked by the arbitrary arrest of several civil society leaders, journalists and bloggers. Eight civil society leaders were arrested and prosecuted following an anti-corruption protest in response to the exposure in March 2020 of corruption within the Ministry of Defence in the procurement of military material. The protest was banned and dispersed by security forces. Restrictive legislation such as the 2019 Law on Cybercrime is also being used against activists and journalists.

Togo’s civic space rating has been backsliding since the crackdown on anti-government opposition protests against the continued control of power by the Gnassingbé family and to demand a return to a two term limit for presidents. Civic space violations since 2017 include the killing of protesters, arrest and prosecution of human rights defenders and pro-democracy activists, banning of civil society and opposition protests, suspension of media outlets, judicial harassment of journalists, regular disruption of and shutting down of access to the internet and social media, adoption of restrictive legislation such as the 2018 Cybersecurity Law and the 2019 modification of the law on conditions and exercise of peaceful meetings and protest. For presidential elections held in February 2020 the accreditation a civil society group to observe the elections was revoked, while access to social media was blocked on two networks.

Positive Developments

In Gabon, in June 2020, the National Assembly adopted an amendment to the Penal Code, decriminalising same-sex relations, a year after these were criminalised, potentially making safer the conditions for organisations defending LGBTQI+ rights. Sierra Leone’s parliament repealed Part Five of the 1965 Public Order Act, which criminalised sedition and libel, on 23 July 2020. The Gambia and Namibia moved closer to having access to information laws, as draft laws were tabled in both countries for consideration by the National Assembly in June 2020. After sustained efforts by media freedom organisations who petitioned the Ombudsperson, Mozambique revoked Executive Decree 40/2018 in May 2020, which set exorbitant fees for the registration, licensing and renewal of licences for media outlets and high fees for the accreditation of local and foreign journalists.

Regional similarities and differences

Across the five regions covered by our analysis, we see common trends, but also some regional differences. For instance, in the Americas, intimidation and harassment are the most commonly reported violations. In Asia and the Pacific, the most common documented tactic is restrictive legislation. Detention of protesters tops the list in Europe and Central Asia. In MENA, the most frequently reported trend is censorship. In Africa, the detention of journalists is the most common civic space violation.