Civic Space on a Downward Spiral

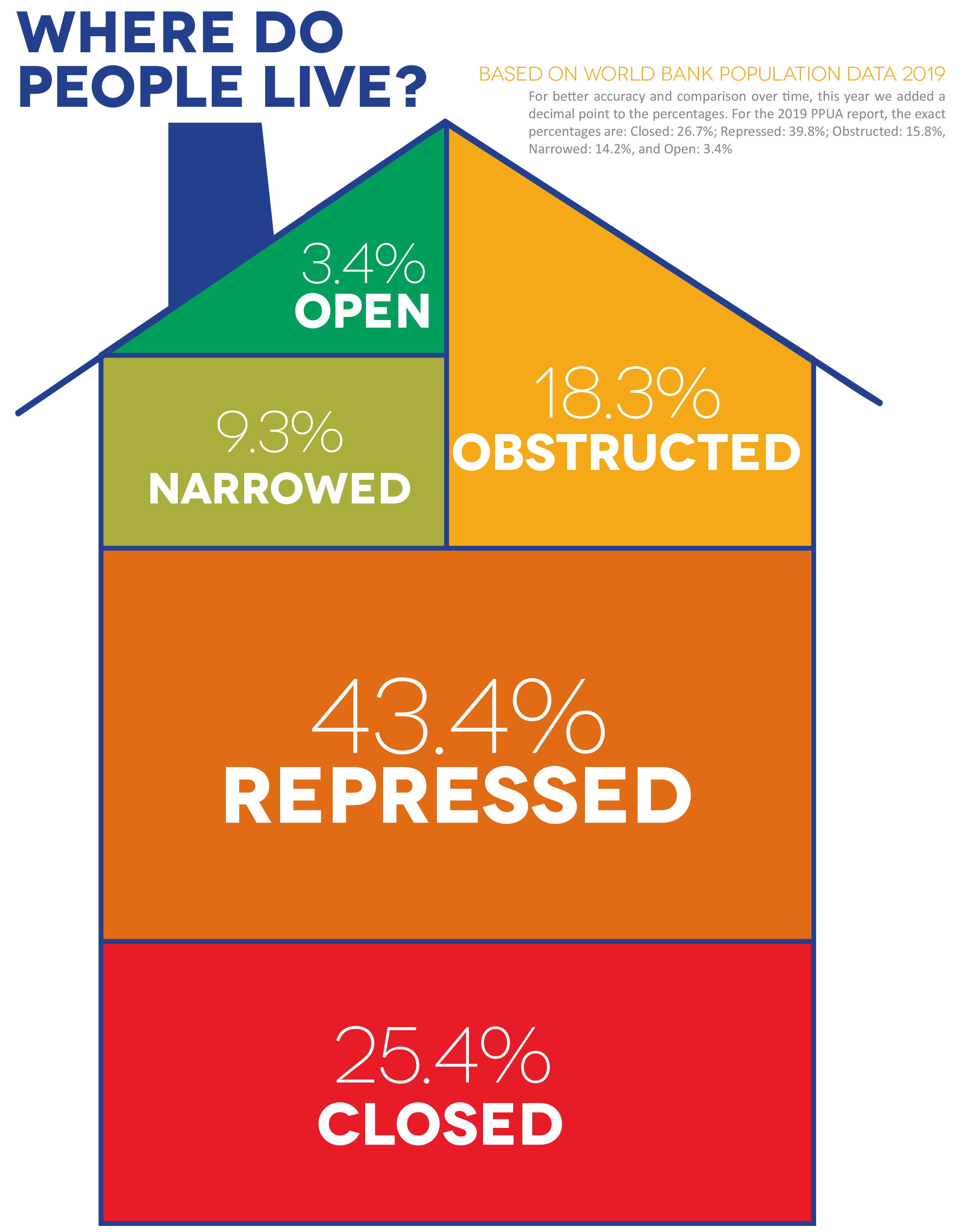

Civic space conditions are declining year on year. In 2020, 43.4 per cent of people now live in countries rated as having repressed civic space, while the percentage of people living in countries with obstructed civic space jumped from 15.8 per cent to 18.3 per cent.

While the number of people living in conditions of closed civic space has lessened, due in large part to some welcome but limited improvements in the DRC and Sudan, the number of people living in countries with serious restrictions has increased as now 87 per cent of the world’s population lives in countries rated as closed, repressed or obstructed.

In 2020, only 12.7 per cent of people around the world live in countries with an open or narrowed civic space rating, a significant decline from the 17.6 per cent who did so in 2019.

The latest update of CIVICUS Monitor ratings in November 2020 indicates that civil society continues to work and operate in an increasingly hostile environment. Our data shows that there are 23 countries with closed civic space, 44 countries with repressed space and 47 with obstructed space, meaning that 114 countries are assessed as having serious civic space restrictions. In comparison, 40 countries are rated as having narrowed civic space and just 42 countries receive an open rating. Since our previous report, published in December 2019, the story is one of further regression: more countries have moved towards the obstructed and repressed categories and there are few where civic space conditions have improved.

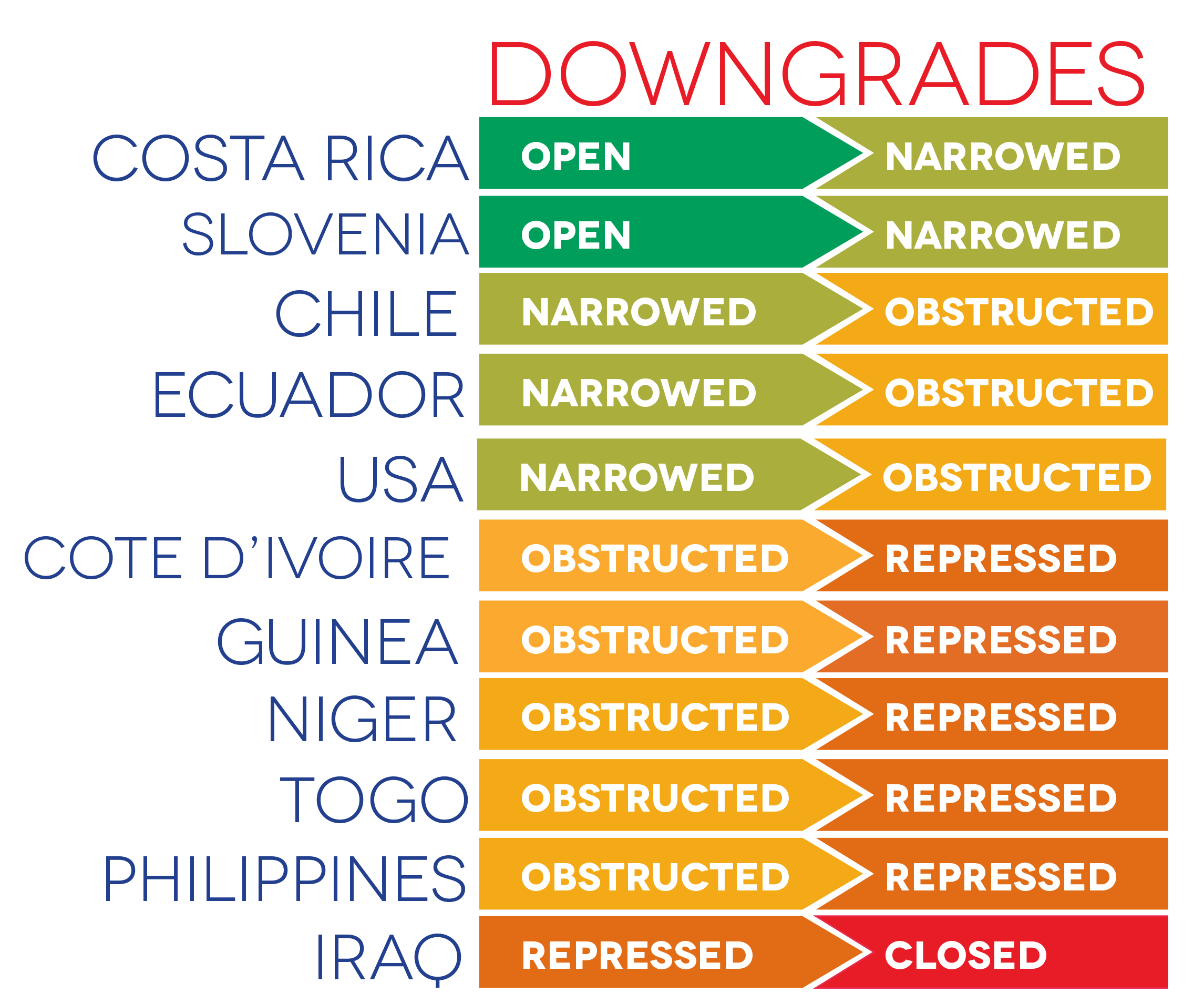

Civic space ratings have changed for 13 countries since our December 2019 update: ratings have improved in only two, while in 11 they have worsened.

In the Americas, our latest analysis shows respect for civic space declining in countries that had previously prided themselves on their performance in upholding fundamental freedoms, or where there had been improvements in previous years. Costa Rica’s civic space rating goes from open to narrowed, while three countries in the narrowed category – Chile, Ecuador and the USA – are downgraded to obstructed.

The decline in civic space conditions in Asia remains a cause of concern. The Philippines moves down from obstructed to repressed, due in particular to the vilification of activists and targeting of human rights defenders and journalists.

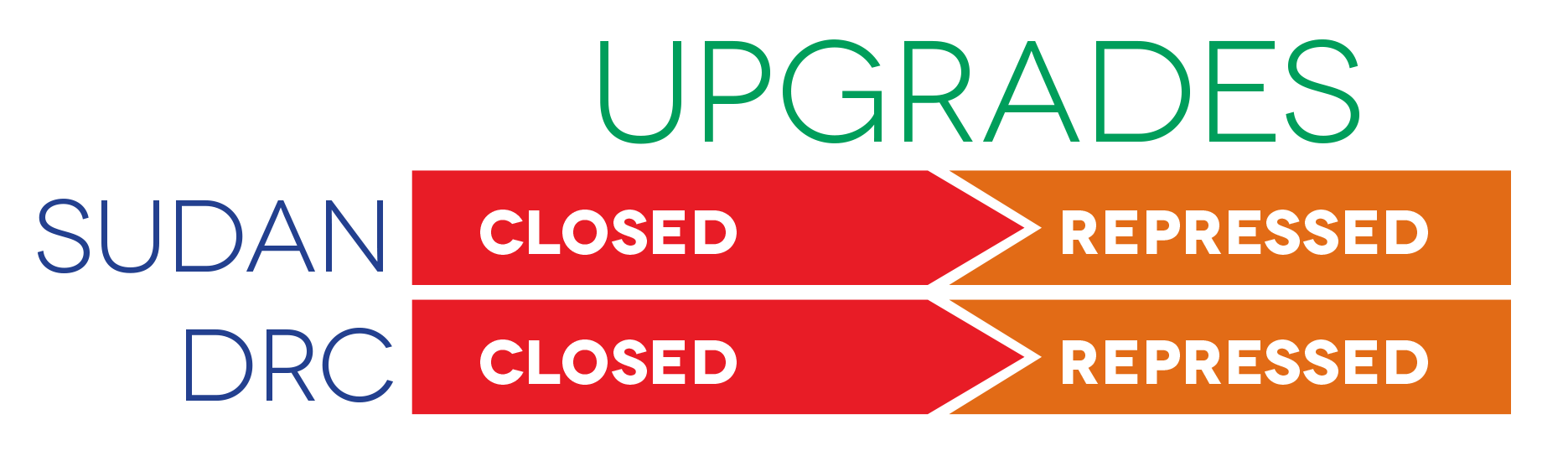

In Africa, and particularly in West Africa, civic space continues to decline, with four countries – Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Niger and Togo – moving from obstructed to repressed. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), some positive steps have been taken since President Félix Tshisekedi took office in January 2019. Although much still needs to be done to break with the systematic human rights violations that characterised the previous administration, some positive steps move the DRC’s civic space rating from closed to repressed. Sudan is also upgraded from the closed category to repressed, as the formation of the transitional government in 2019 and initial reform efforts have improved the civic space situation.

Europe is the region with the most open countries, but the situation still shows decline as Slovenia moves from an open to narrowed rating. In more positive news, following a change of government, which led to more improved relations with civil society, Austria’s rating moved from narrowed to open in October 2020.

MENA, the region with the most countries in the closed category, adds one more to the list, with Iraq moving from repressed to closed as the country continues to experience an extensive crackdown on the freedoms of peaceful assembly and expression in reaction to the ongoing popular protest movement.

COVID-19: a pretext for repression

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic. Governments across the world began taking extraordinary measures and enacting emergency legislation, with the stated aim of protecting people’s health and lives. While limitations on rights are allowed by international law in response to health emergencies, international law is clear that those limitations must be proportionate, necessary and non-discriminatory. However, our research suggests that repressive governments used the pandemic as an opportunity to introduce or implement additional restrictions on civic freedoms.

2019 had been a year of protests as growing inequality, dire economic conditions and the urgent need to demand fundamental rights led people across the world to the streets. In 2020, people continued to mobilise, using creative and alternative forms of protest, including online and masked and distanced protests. Despite the pandemic, urgent demands for rights brought people onto the streets to demand political and structural change, including in Chile, Hong Kong and Nigeria. In the USA, massive protests to demand racial justice and police accountability erupted across the country following the killing of George Floyd, a Black man, by a Minneapolis police officer; many others around the world joined their cause and drew attention to their own issues of racial injustice. In Belarus and Kyrgyzstan people joined protests for free and transparent elections after their democratic freedoms were denied. As the pandemic further exacerbated already dire economic conditions in many countries, people raised their voices to demand food, basic services and better working conditions in many countries, including Venezuela and Zimbabwe.

Rather than addressing the root causes of people’s discontent, governments often focused on curtailing rights and meting out repression. According to the 516 CIVICUS Monitor updates over the period covered by this report, the fundamental right to peaceful assembly continues to be under attack. Our data shows that the detention of protesters and the excessive use of force against them are the most common tactics being used by governing authorities to restrict the right to peaceful assembly. This is not a new trend; it was consistently seen during 2019, but what changed in 2020 was that multiple governments used the pandemic as an excuse to restrict democratic activities and challenge civic freedoms.

It was ironic, given the pandemic, that the main tactic governments used to discourage and punish people who took to the streets was detention, meaning that they often took people from open public spaces and locked them in closed and frequently overcrowded prisons, conditions that could only exacerbate the spread of the virus. International mechanisms have consistently advised that any penalties applied to people who challenge restrictions should not contribute to the further spread of infections. The use of detention as a widespread tactic calls into question whether governments were always genuinely motivated by a need to ensure public health or if instead COVID-19 was used as a pretence to crack down on protests.

The protests triggered by the killing of George Floyd in the USA were met with excessive force by militarised police and security forces. The authorities, including President Donald Trump, fuelled the violence by encouraging law enforcement officers to respond forcefully. In a particularly notorious case, the Attorney General ordered the use of teargas against peaceful protesters with the sole purpose of allowing the President to take a picture near a local church. The use of teargas has led health experts to note that these chemicals compromise people’s health at a time when the world is dealing with a respiratory virus.

In France, in May 2020, the government enacted a ban on peaceful assembly as a result of sanitary emergency measures to tackle the pandemic. While the Council of State limited the ban to protests of over 5,000 people a month later, the authorities used teargas to disperse protests. Even before the pandemic had been declared, excessive force was used by the authorities against feminist protesters who were teargassed and beaten by police.

In Thailand, since the beginning of 2020, thousands of people have marched to demand the dissolution of Thailand’s military-backed government, the drafting of a new constitution and an end to the harassment of activists and government critics. The authorities responded by harassing and detaining protesters, physically blocking access to protest sites, shutting down transportation and in some instances dispersing protests with excessive force.

In Guinea, protests and activism against the replacement of the 2010 Constitution were met with excessive use of force. Dozens of protesters were killed. There were also extensive arbitrary arrests and prosecution of human rights defenders and protesters.

Repression of protests took place regardless of the underlying level of freedom experienced by civil society. The CIVICUS Monitor documented the detention of protesters and the use of excessive force to disperse and disrupt protests in countries with closed or repressed ratings, such as Azerbaijan, Belarus, Djibouti and Uganda, but also in countries where people typically have been able to exercise their freedoms without major hindrance, such as Belgium and Sweden. The detention of protesters was one of the main tactics used in countries classed as having open civic space.

An information blockade

“Censorship can kill, by design or by negligence,” stated the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on the Freedom of Opinion and Expression in her latest report, emphasising the importance of the free flow of information for the protection of life and health.

However, the expression of dissent, work to hold decision-makers accountable and the ability to share and disseminate information freely continue to be the enemy of many governments: censorship features prominently in the 516 civic space reports published in this period. This tactic is commonly associated with the harassment and intimidation of activists and attacks on journalists, which also rank among the top violations documented. This trend confirms the worrying developments reported last year, when censorship flourished as the main tactic used by governments to stifle dissent.

Some governments used the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to silence critical voices. The authorities in China, which for decades have targeted the freedom of expression, continued their path of repression, censoring numerous articles and social media posts about the pandemic, including those posted by families of infected people seeking help. In Turkey, where free speech was under siege before the pandemic, the government inspected over 6,000 social media accounts for COVID-19-related posts, detained hundreds of people and passed a restrictive law to censor social media. In Vanuatu, it was announced that it would be illegal for media outlets to publish any articles on COVID-19 without first receiving authorisation by the authorities. In Tanzania, multiple media outlets and journalists faced a backlash for reporting information challenging the official narrative on COVID-19, which consistently downplayed the seriousness of the pandemic.

Even before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, countries were passing legislation to criminalise speech under the guise of preventing the dissemination of ‘fake news’. In Vietnam, the government announced it had requested Facebook to ‘pre-censor’ online content and remove advertisements “that spread fake news related to political issues upon request from the government.” Similarly, in Singapore, the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act is increasingly being used to target the opposition and critics.

Another common tactic the authorities use to prevent the dissemination of critical information is internet shutdowns or the blocking of access to social media, especially during elections or mass protests. In 2020 this tactic was used in Bangladesh, Chad, Ethiopia, India and Palestine, among other countries.