Europe & Central Asia

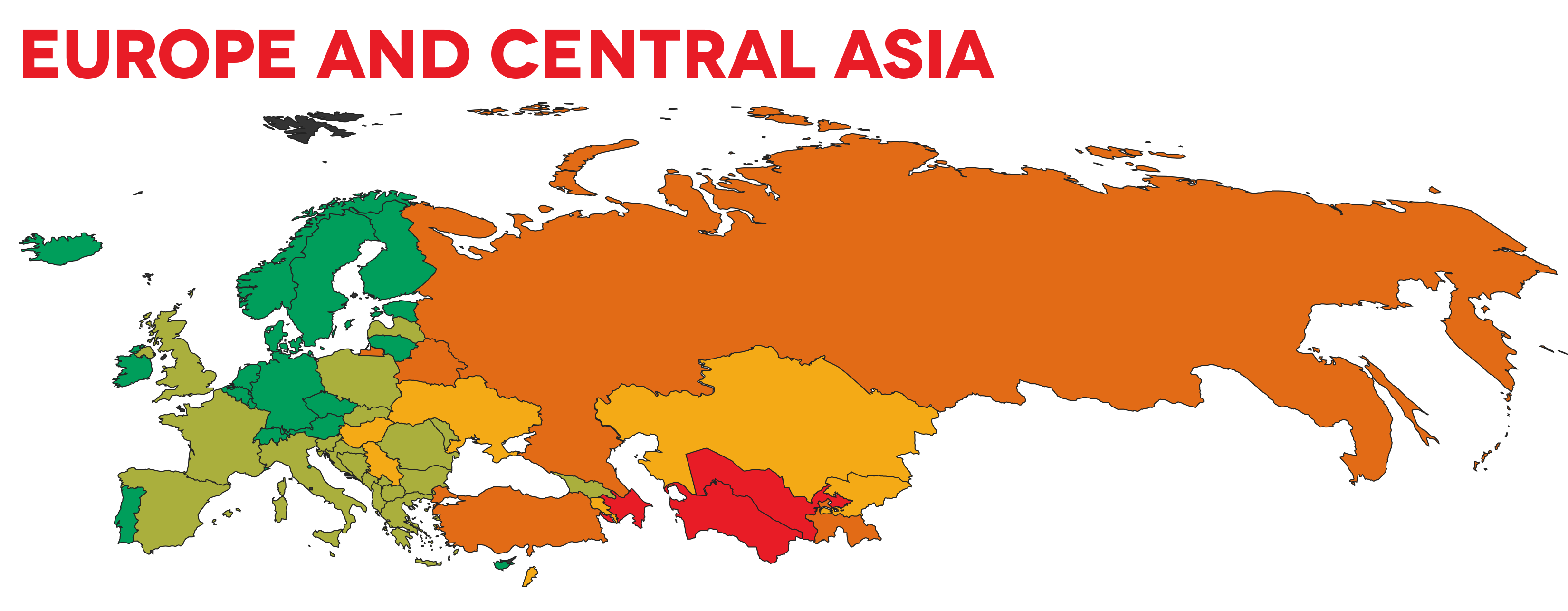

There have been no major improvements in civic space in Europe and Central Asia since the previous report. Of the region’s 54 countries, civic space is rated as open in 21 countries, narrowed in 20, obstructed in six, repressed in four and closed in three. Governments in Central Asia continue to repress civic space, while Europe is seeing a decline in civic freedoms. In the past year, there has been a notable decline in the quality of civic space in Slovenia, with improvements noted only in Austria.

Ratings Overview

The downgrading of Slovenia’s rating from open to narrowed reflects a significant worsening of civic space under Prime Minister Janez Janša, who came to power in March 2020 and is known for his anti-migration views and criticism of the media. The government has taken steps to diminish media independence with outlets such as Nova24 TV, Nova24 online and Planet TV increasingly being funded by people connected to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, a close ally of Janša, and known for eroding the space for independent media in Hungary. The new government has introduced a package of three media laws that may lead to political interference over media management appointments. CSOs in the cultural sector have also come under threat, with several facing eviction at the time of writing. Since March 2020, people in Slovenia have staged Friday bicycle protests against the government.

A GLOOMY PICTURE FOR CIVIC SPACE

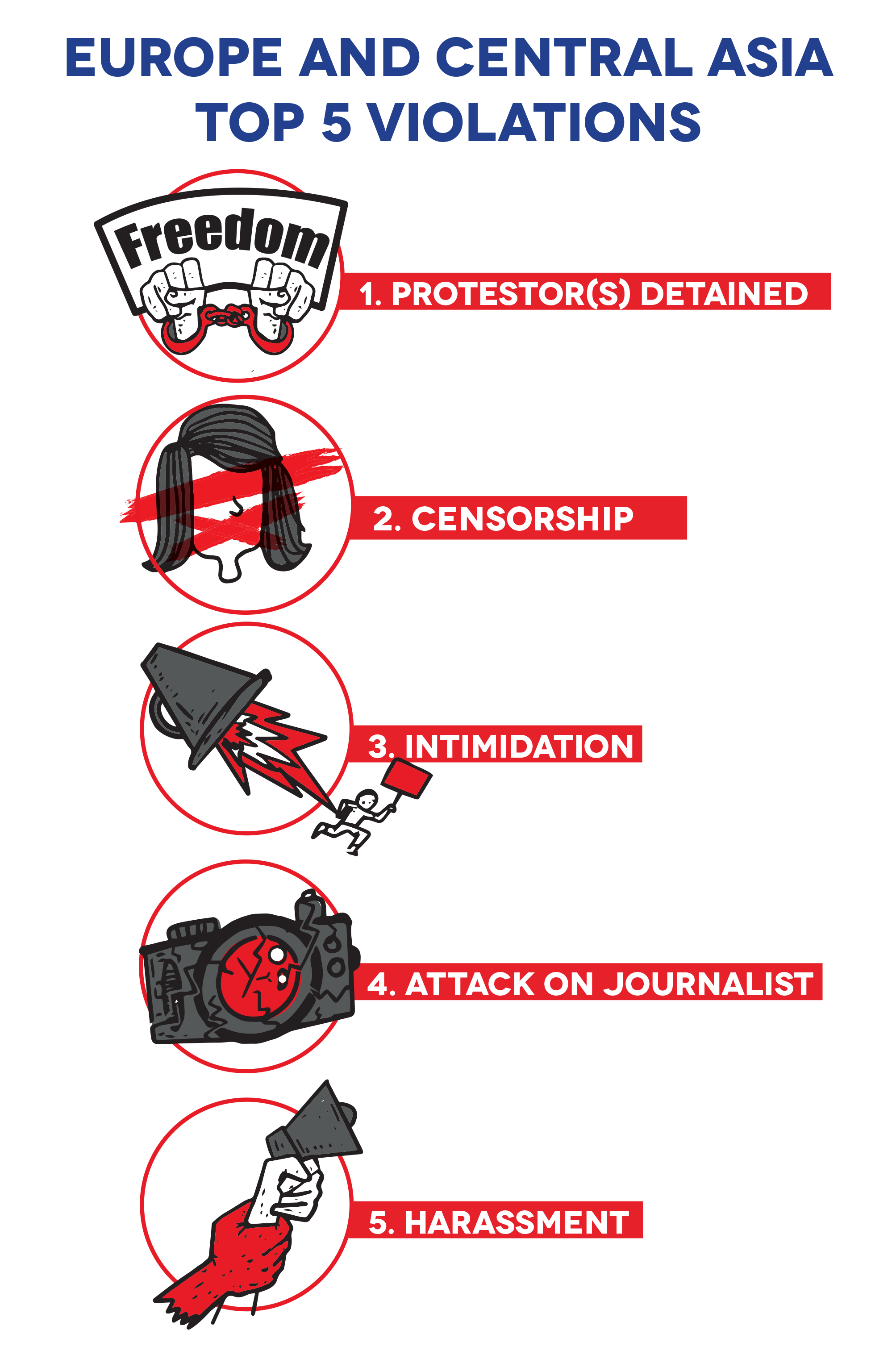

Major restrictions on civic space in the region include repression of protests through excessive force and detention of protesters, censorship of journalists, activists and CSOs, intimidation and harassment and the passing of restrictive laws. Over the past year, threats to the freedom of expression and the targeting of women and LGBTQI+ groups are some of the key trends documented in the region.

In Germany, journalists faced verbal attacks during protests against COVID-19 measures. Journalists in France have been obstructed in doing their jobs through intimidation and detention while covering protests. Journalists also continue to face threats from the far-right Vox party in Spain. In response to the spread of misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic, journalists in Croatia launched a fact-checking blog, but this left them on the receiving end of harmful speech on social media. In Montenegro, a new Media Law forces journalists to reveal their sources at the request of the Prosecutor's Office.

Civic space incidents involving women and LGBTQI+ groups are growing in various parts of Europe. Violations against these groups are often fuelled by far-right groups, a trend noted in our 2019 report that continues to have a negative impact upon civic space. In Hungary, despite numerous appeals from transgender rights groups amid the pandemic, the government passed an amendment to the Registry Act that only recognises ‘sex at birth’, outlawing legal recognition of transgender and intersex people. In Poland and Turkey, the governments have indicated that they intend to withdraw from the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence, known as the Istanbul Convention, resulting in massive protests led by women. These developments will further restrict the space for CSOs working on women’s and LGBTQI+ rights. Attacks on LGBTQI+ rights have also been documented in Italy, Lithuania, North Macedonia and Romania.

Civic space remains under threat in Central Asia, where the COVID-19 pandemic has been used as a pretext to impose further restrictions. The governments of Tajikistan and Turkmenistan both initially denied the existence of COVID-19 in their countries and instead increased restrictions on the freedom of expression. In Turkmenistan, the government’s effort to cover up the COVID-19 outbreak included threatening medical workers with repercussions for speaking out about COVID-19-related cases. In neighbouring Tajikistan, the government targeted independent media for ‘spreading panic’ and attempted to stifle discussion of the pandemic by introducing a new law to punish people for distributing ‘inaccurate’ and ‘untruthful’ information about COVID-19 through the press or through social and electronic networks. In the name of fighting ‘false information’ about the pandemic, the authorities in other Central Asian countries have also introduced and implemented broadly worded legislation that restricts legitimate free speech.

The political future of Kyrgyzstan currently hangs in the balance, following post-election protests that plunged the country into a political crisis. The 4 October 2020 parliamentary elections were marred by allegations of widespread irregularities that ignited mass protests by opposition members and supporters. Law enforcement officers responded harshly to protesters and violence was used by non-state groups. Protesters managed to break in and occupy the White House, which is the seat of the president and parliament. Groups also unlawfully released previous high-profile political figures from prison, including Sadyr Japarov, a former member of parliament. The post-election protests resulted in a swift change, with Japarov sworn in as both acting president and prime minister, after the resignation of President Sooronbay Jeenbekov. Japarov has since stepped down to run for early elections that are set for 10 January 2021.

Civic Space Restrictions

Violations in the region most frequently documented by the CIVICUS Monitor during the reporting period were the detention of protesters, censorship, intimidation, attacks on journalists and harassment.

Protesters detained

In 2020, the detention of protesters was the most frequent violation, documented in at least 30 countries.

In Belarus, the mass detention of protesters, which began ahead of the August 2020 elections, continued after anti-government protests erupted following highly disputed election results in which the incumbent, President Alexander Lukashenko, was declared the winner. Thousands were arrested throughout August and September 2020 and detentions are continuing. In Serbia, anti-government protests took place shortly after parliamentary elections, boycotted by the opposition, in June 2020, following the government’s reintroduction of a COVID-19 curfew. Peaceful protests attended by thousands of people around Serbia turned violent due to alleged provocation from civilian groups, with law enforcement officers using excessive force and detaining protesters. In Azerbaijan, people including activists, opposition groups and their supporters took to the streets to dispute the parliamentary election results. In February 2020, police detained 20 protesters at one protest and pre-emptively detained another 100 activists prior to another demonstration. Detention of protesters during anti-government protests continued in the months that followed, and also in relation to protests around the Azerbaijan-Armenia conflict that began in July 2020. Around 90 protesters were detained in Armenia after supporters of Gagik Tsarukyan, leader of the Prosperous Armenia Party, staged a protest in front of the national Secret Service headquarters.

The detention of climate protesters has also been documented in some countries. In France, climate activists who staged a protest at the G7 summit were met with 13,000 police officers who secured the area to prevent protests and arrested over 100 protesters. About 40 Extinction Rebellion climate protesters were arrested in Oslo, Norway, after staging protests over the government’s failure to deal with the climate crisis. In the UK, police arrested climate activists, including with pre-emptive detentions, for organising and staging the ‘Heathrow Pause’, a civil disobedience protest that involved flying a drone within the airport’s exclusion zone to disrupt flights.

Censoring critical voices

Freedom of expression remains under threat in the region, with COVID-19 being used as a pretext to further restrict free speech. Censorship was documented in at least 25 countries in Europe and Central Asia.

In Hungary ‘false information’ on the pandemic was criminalised by a new law, with penalties that include jail sentences of up to five years. Media independence hangs by a thread due to relentless political interference by Prime Minister Orbán’s government. The entire editorial staff of Index.hu, which was Hungary’s leading independent news site, resigned due to proposals to compromise its editorial independence. Hungary’s Media Council failed to extend the licence of the Klubrádió radio station, one of the few remaining critical outlets.

In Turkey, where free speech was under siege before the pandemic, the government interrogated people associated with over 6,000 social media accounts for COVID-19 related posts and passed a restrictive law to censor social media.

Media freedom has come under greater threat in the UK in the last year, particularly during the pandemic. An Open Democracy reporter was banned from asking questions during briefings, while other reporters were met with restrictions when covering the daily COVID-19 media briefings provided by the prime minister and other officials.

Intimidation

The use of intimidation as a tactic to deter journalists, CSOs and human rights defenders was documented in at least 29 countries in Europe and Central Asia. In particular, several cases of intimidation of women journalists were documented in the Balkan region, with threats often gendered in nature. In North Macedonia, a woman journalist received messages via Facebook and Twitter containing verbal abuses and hate speech. She received dozens of messages threatening her with rape as well as death in response to her work. In Bosnia and Herzegovina a woman journalist was threatened for reporting on an environmental rights story. In Bulgaria, a woman journalist, whose story portrayed a far-right group in a negative light, had to flee the country with her family after allegedly receiving threats from unknown people against her and the family, with her personal information leaked online.

In Serbia, CSOs and journalists who are critical of the government continue to face intimidation. One recent attack came in the publication of a list of CSOs and journalists to be probed for links with money laundering and terrorism.

Dozens of people, including journalists, bloggers, civil society activists, protest participants and others critical of the authorities, are frequently subjected to intimidation, pressure and court-imposed obstacles in Kazakhstan.

Country of concern: Poland

In the last five years, under the governance of the ruling Law and Justice party (PiS), Poland has seen a rapid decline in civic space. The ruling party has undermined the rule of law and judicial independence, which has had a negative impact on fundamental civic freedoms. The government has increased its anti-LGBTQI+ agenda, with a third of Polish municipalities adopting resolutions ‘against LGBTQI+ propaganda’ and declaring themselves as ‘LGBT-free zones’. During the presidential election, which took place in June and July 2020, incumbent President Andrzej Duda ramped up his anti-rights rhetoric, remarking that LGBTQI+ individuals are “not people, but an ideology.” LGBTQI+ activists have faced persecution, with the separate arrest of three LGBTQI+ activists who hung up rainbow flags, on charges of offending religious feelings.

Massive protests erupted in October 2020 and continue at the time of writing, following a ruling by the Constitutional Tribunal to impose a near-total abortion ban, in a country that already has one of the strictest abortion laws in the European Union. Protesters were met with excessive force from law enforcement officers and violence from far-right groups.

Media freedom in Poland is also under threat, with PiS targeting independent media outlets such as Gazeta Wyborcza with dozens of lawsuits to intimidate and censor its critical coverage. Poland’s public television station Telewizja Polska has repeatedly been used as a government mouthpiece. Draft legislation targeting foreign-funded CSOs is also on the table, posing a major threat to the freedom of association. The government states the purpose of such a law is to fight CSOs that serve foreign interests.

Positive Developments

Increasing dialogue between government and civil society in Austria has led to an improvement in civic space, offering a much-needed positive story for the region. In an unprecedented move, the Austrian government passed COVID-19 legislation that recognised the role of CSOs and introduced a special grant package providing additional support for CSOs during the pandemic. The improvement in the space for civil society is due to political change, with the CSO-friendly Greens party replacing the extreme far-right Freedom Party Austria (FPÖ ) in a coalition with the Peoples Party (ÖVP).

Regional similarities and differences

Across the five regions covered by our analysis, we see common trends, but also some regional differences. For instance, in the Americas, intimidation and harassment are the most commonly reported violations. In Asia and the Pacific, the most common documented tactic is restrictive legislation. Detention of protesters tops the list in Europe and Central Asia. In MENA, the most frequently reported trend is censorship. In Africa, the detention of journalists is the most common civic space violation.