Americas

The year tested civil society in the Americas more fiercely than any in recent times. At the end of 2019, the region shook with the echoes of protesters flooding the streets. In Chile, which bewildered the world with a harsh crackdown on protesters, there was a sense of growing momentum despite government repression. But by March 2020, movement restrictions and bans on public gatherings started to be implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

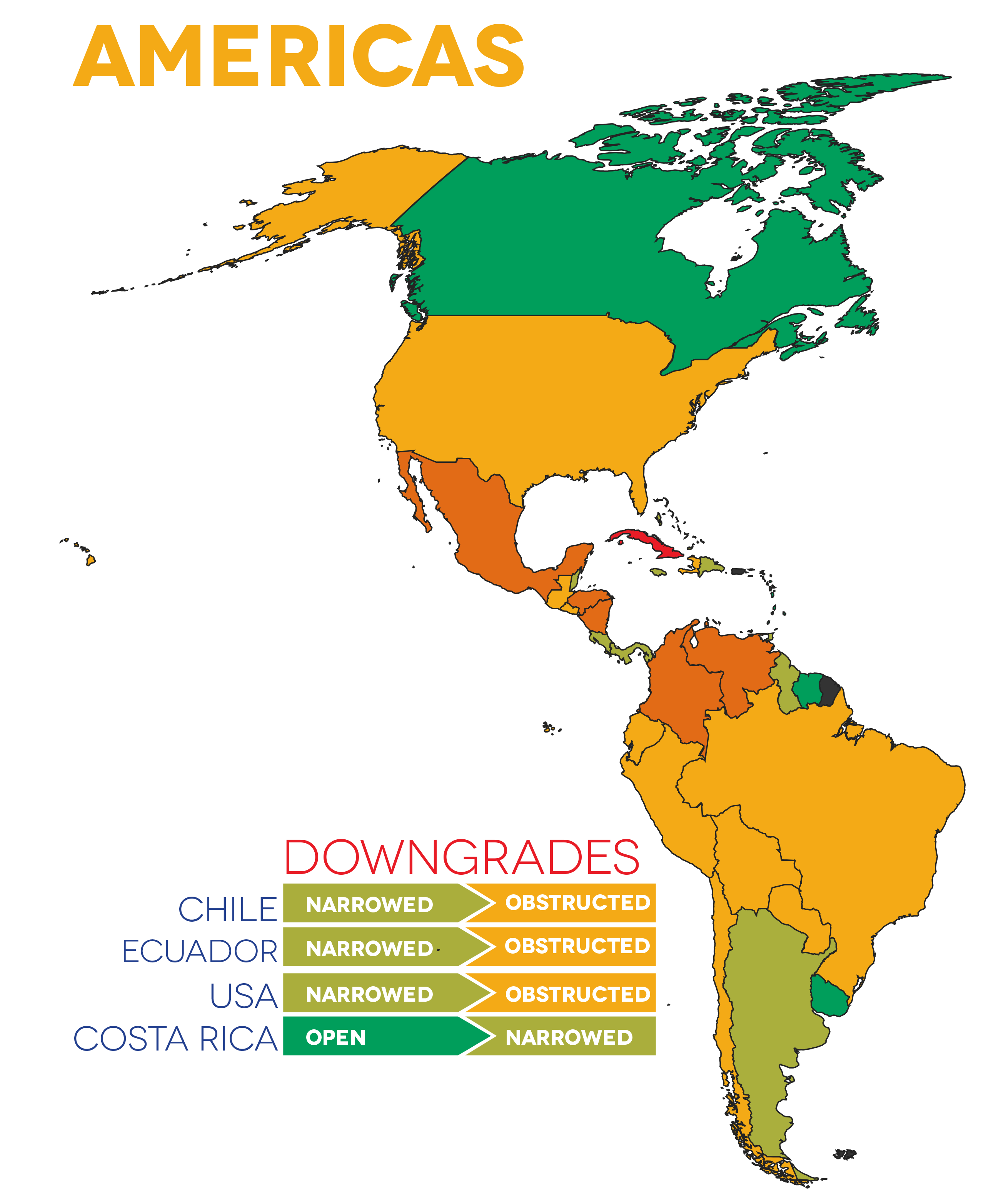

Ratings Overview

On first sight, the overall picture looks bleak in the region, given significant declines in four countries where civic freedoms had previously been well respected, with Costa Rica’s rating moving from open to narrowed, and three countries – Chile, Ecuador and the USA – declining from narrowed to obstructed. The CIVICUS Monitor now rates civic space as open in only 10 of the 35 countries of the Americas, as narrowed in nine and as obstructed in another 10 countries. Civic space remains repressed in five countries of the region and closed in one, Cuba.

These ratings changes partly reflect the scale of repression as mass protest movements erupted. In the USA, militarised law enforcement officers detained thousands, fired teargas and projectiles indiscriminately and consistently attacked journalists during protests against racism and police brutality. The country’s downgrade also indicates a longer process of sustained deterioration in the freedom of expression and the chipping away at civil liberties by, for instance, the introduction of time and place restrictions to criminalise protests.

In Chile and Ecuador, the authorities failed to reckon with widespread violations committed by law enforcement officers during protests, with the government of Ecuador rejecting a report documenting hundreds of testimonies of violence experienced by protesters. Instead, Ecuador’s government has sought to pass legislation further enabling excessive force. Additionally, Ecuador’s steps forward in media freedom proved fragile, with stigmatisation and attacks on journalists increasing once again. Ecuadorian media freedom advocates documented that freedom of expression violations more than doubled in 2019 compared to 2018. In Chile, police continued to repress protests even as they became sporadic during the pandemic and tried to criminalise feminist activists. In the La Araucania region, Indigenous Mapuche peoples also reported increasing oppression against their communities.

Indigenous rights defenders in Costa Rica also faced a surge in attacks, with a human rights defender killed and several others violently assaulted. Dozens of protesters were detained after protests against proposed new tax measures began in September, and the authorities have sought to persecute protest leaders. Early in 2020, Costa Rica also enacted regulation limiting strikes, approving a proposal introduced to curb demonstrations after mass mobilisations took place in 2018.

Yet even where a decline has taken place, civil society has reasserted itself. When governments attempted to enact overly broad legislation with the pandemic as a pretence, as in Bolivia and Honduras, civil society successfully pushed back against legislative abuses. In Chile, millions of people voted to launch a convention to draft a new, more democratic constitution. The period covered in this report has therefore been one of a constant battle for civic space in the Americas.

“They are killing us”: defenders’ lives at risk

As Colombia’s government declared a sanitary emergency and established a nationwide quarantine, human rights defenders found themselves at increased risk. Common security strategies, such as varying travel routes, became impossible, making social leaders and journalists more vulnerable. Meanwhile, territorial disputes between armed groups continued while the government stalled on the implementation of Colombia’s peace process. Rising violence has claimed the lives of dozens of human rights defenders.

While the Colombian situation is arguably the most extreme, the country is far from an isolated case. The CIVICUS Monitor documented cases of the killing of human rights defenders in 11 Latin American countries: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua and Peru. Taking a global perspective, the regional violence is even more shocking: the Americas accounted for over 60 per cent of all reports of killings of human rights defenders documented by the CIVICUS Monitor during the reporting period.

Indigenous leaders and land and environmental defenders continue to be particularly at risk in the Americas. In Honduras, a young environmental defender was killed shortly after telling national protection authorities that he feared for his life. Garífuna communities in Honduras have repeatedly denounced the systematic killings of their leaders, which continued in 2020. Time and again, across the region in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Peru, Indigenous leaders were killed after speaking up about threats to themselves and their communities.

Persistent impunity for these crimes, with those suspected of commissioning killings left untouched even in relatively high-profile cases such as that of the assassination of Berta Cáceres, continues to embolden violence against human rights defenders in the region.

Civic Space Restrictions

In the Americas, the civic space violations most frequently documented by the CIVICUS Monitor in this period were intimidation, harassment, attacks on journalists, detention of protesters and the excessive use of force against protests.

Intimidation and harassment

Intimidation tactics use fear to deter human rights defenders and journalists from continuing their work. Harassment has the same strategy and goal but is characterised by the repeated targeting of a person. They often go hand in hand, encompassing a wide range of tactics such as threats, smear campaigns and recurrent police summonses. Between November 2019 and October 2020, intimidation and harassment took place in at least 22 of the 35 countries of the Americas.

These violations were particularly prevalent in Honduras and Nicaragua. Activists and government supporters were besieged in their homes by hostile civilian groups and police officers in Nicaragua. Critical journalists faced smear campaigns and even Nicaraguan journalists in exile experienced terrorisation through threats to family members who remained in the country. In Honduras, the CIVICUS Monitor recorded several cases of online and offline defamation campaigns and death threats against journalists and human rights defenders. In both countries, as well as in Brazil, El Salvador and Guatemala, CSOs highlighted a pattern of women human rights defenders and journalists being targeted by misogynistic smear campaigns in retaliation for their work.

Meanwhile in Cuba, new internet regulations were instrumentalised to intimidate dissidents and further curtail the freedom of expression. At least 30 people reported receiving police summonses from Cuban authorities, being subjected to interrogations and threatened with fines or detention if they did not stop their work. In Argentina, journalists reported facing stigmatisation by the new government just as investigations exposed the former government’s extensive surveillance of critical voices, highlighting a lack of respect for media freedom that goes deeper than individual government administrations.

Attacks on journalists

Assaults on communicators and media outlets were documented in 15 countries in the Americas, occurring in over 40 per cent of CIVICUS Monitor reports in this period. Such attacks were perpetrated by both state and non-state forces seeking to silence and inhibit the media.

These incidents often took place as journalists covered protests. In the USA, media freedom advocates documented over 100 cases of reporters being assaulted during mass protests against racism. In many cases these attacks were perpetrated by law enforcement officers using indiscriminate force, including cases of officers shooting, assaulting and detaining journalists wearing media credentials. In Bolivia, political polarisation meant local and international correspondents endured verbal and physical attacks from protesters across the political spectrum.

In addition, journalists in the Americas were subjected to attacks for speaking truth to power and reporting on corruption, crime and the COVID-19 pandemic. By May 2020, press associations in El Salvador had registered over 40 reports of journalists who had been attacked for seeking and sharing information on COVID-19. In Mexico, which remains one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, attacks and killings of journalists often took place in broad daylight. Worryingly, in 2020 at least two journalists were killed in Mexico while under police protection, in attacks that sometimes also claimed the lives of their bodyguards. This underscored the deficiency of the country’s protection mechanism.

Detention of protesters and excessive force

Outrage at political and economic conditions and hope for change brought people to the streets across the Americas. During this research period, the CIVICUS Monitor documented protests in 25 countries of the region. Protests took place in both more open and more repressed conditions, often in defiance of the authorities’ lack of respect for civic freedoms and brutal government responses.

Protests expressing anger at social conditions and lack of government support during the pandemic were frequently met with repression. In Venezuela, protesters were detained for demanding basic goods and public services in rural areas. In Paraguay, police reportedly used firearms against people demanding that quarantine measures be made more flexible. Peru’s government proposed legislation to enable the use of force against protesters as officers teargassed and detained people who were asking that labour rights be respected during the crisis.

In 2020, some leaders used sanitary measures to cloak the suppression of protests with a veneer of legitimacy. In Bolivia and Panama, for instance, protesters were detained and charged for protocol violations while demanding aid during COVID-19. In the Dominican Republic, police claimed protesters against racism had been detained for violating social distancing rules, even though a nationalist protest on the same day was allowed without disruption.

Yet the Monitor documented widespread violations both before and during the pandemic. Protesters were detained in almost half of all CIVICUS Monitor reports documenting protests in the region during this period. Over 10,000 protesters were detained in Chile between October 2019 and January 2020, according to data from the country’s National Human Rights Institute. In Cuba and Nicaragua, the detention of protesters was systematically used as a tactic to demobilise dissident movements. Mexican feminist marches were repressed before and during the pandemic, and human rights organisations denounced police using tactics that could amount to enforced disappearances of protesters.

In the USA, news outlets reported that about 9,000 people were detained within the first 10 days of mass protests against racism and police brutality. The USA’s astounding crackdown on protesters by militarised law enforcement officers included hundreds of incidents of protesters being beaten, indiscriminate use of teargas and less-lethal weapons and crowd control methods that escalated tensions rather than protected public safety. In Colombia, people protesting against state violence were also met with brutality: security forces used firearms indiscriminately and over two nights of demonstrations at least 10 people were killed and 140 detained.

Country of concern: Brazil

The first two years of the government of President Jair Bolsonaro have tested the vitality and resilience of Brazil’s civil society. Attacks from government against the freedoms of association and expression have taken a range of forms, including public vilification of CSOs, criminalisation of activists and attempts to monitor critics and delegitimise the media. Indigenous communities and environmental and land rights defenders have become increasingly vulnerable to attacks, as the government emboldens illegal loggers, miners and land grabbers. Activists and social movements are doing their best to resist, and have campaigned, mobilised public opinion and fought in court to push back against repeated attempts to restrict civic freedoms, reduce social participation and subvert democratic institutions.

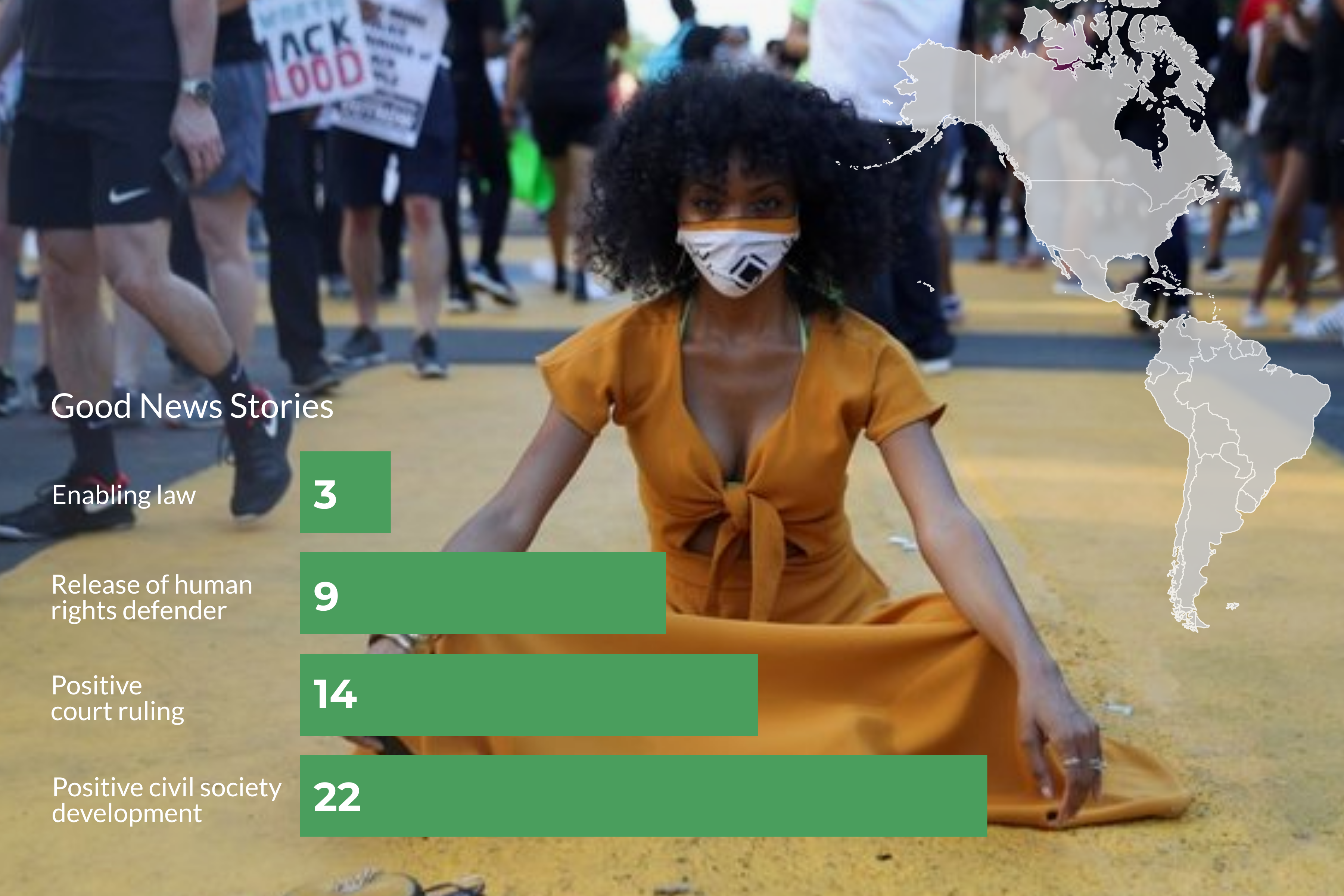

Positive Developments

Protesters made their voices heard even when met with repression, forcing leaders to face public indignation and pushing core issues to the centre of political debate. Black Lives Matter protesters in the USA advanced state and local police reform policies, drove several authorities to re-evaluate their standards on the use of force in protests and heightened pressure for justice in cases of killings of Black and Brown people by law enforcement officers. They also reignited a global movement for racial justice and inspired protesters across the continent and further afield. Meanwhile in Bolivia, sustained pressure from protests and civil society forced the government to schedule and hold presidential elections. The country’s peaceful transition of power offered some hope that less conflictual times could lie ahead.

Chile’s protesters also evidenced the power of mass mobilisation. In October 2020, nearly a year to the date of the first protests, the country held a referendum on the creation of a convention to draft a new constitution. This was the culmination of months of political negotiation, in which civil society movements were prominent. The vote gave a clear mandate to establish a democratic body to develop a new constitution, with an unprecedented commitment to gender parity in its membership, as a result of civil society advocacy. Reserved seats for representation of Chile’s long-excluded Indigenous peoples are also expected.

In November 2020, Mexico became the 11th country to ratify the first regional environmental human rights treaty, known as the Escazú Agreement. This means the landmark agreement, which was negotiated with civil society participation and provides human rights defenders with tools to hold governments to account, will enter into force in early 2021. Peru’s human rights defenders also made important gains as national human rights organisms created new protocols and guidelines for their protection. In addition, civil society won important battles in court: in Canada, courts upheld recently introduced legislation to ban strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs) and ensured protections for journalistic sources; in Brazil, civil society challenged authoritarian policies at the Supreme Court and 18 young people who had been detained before an anti-government protest were acquitted after several years of facing charges.

Regional similarities and differences

Across the five regions covered by our analysis, we see common trends, but also some regional differences. For instance, in the Americas, intimidation and harassment are the most commonly reported violations. In Asia and the Pacific, the most common documented tactic is restrictive legislation. Detention of protesters tops the list in Europe and Central Asia. In MENA, the most frequently reported trend is censorship. In Africa, the detention of journalists is the most common civic space violation.