Middle East & North Africa

No major improvements in civic space in the MENA region have been documented over the past year, indicating that the conditions for civil society remain very challenging.

Ratings Overview

No major improvements in civic space in the MENA region have been documented over the past year, indicating that the conditions for civil society remain very challenging. As states double down on the crackdown on civic space, human rights defenders, journalists and other activists continue to bear the brunt of authoritarian excesses. In Iraq and Lebanon, year-long protest movements have brought further civic space violations. Activists, including the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) most prominent human rights defender, Ahmed Mansoor, remain in prison while in Saudi Arabia, 13 women’s rights defenders are still in jail following a series of arrests of those who stood up for the rights of women that started in May 2018. While rights groups in Iran advocated for detained human rights defenders to be freed as prisons posed a heightened risk of COVID-19 infection, only three women human rights defenders were freed as a result, partially or fully, of the virus: Nargess Mohammedi and, on a temporary basis, Nazanin Zaghari Ratcliffe and Nasrin Sotoudeh. In Bahrain, human rights activist Nabeel Rajab was finally freed from jail in June 2020, after being in detention since 2016 for peacefully expressing his opinions on Twitter, but must still serve out the remaining three years of his sentence at home. Many others remain at risk of contracting COVID-19 in prison. In Palestine, journalists face arrest and detention by both domestic and Israeli forces, andin Yemen, these dangers come from both sides of the conflict. The rights of migrant workers continue to be severely violated in the region, with states such as Qatar denying workers’ basic rights and freedoms including the right to form unions. Across the region, the repression of women and those advocating for women’s rights continues, including in Iran, Egypt andSaudi Arabia.

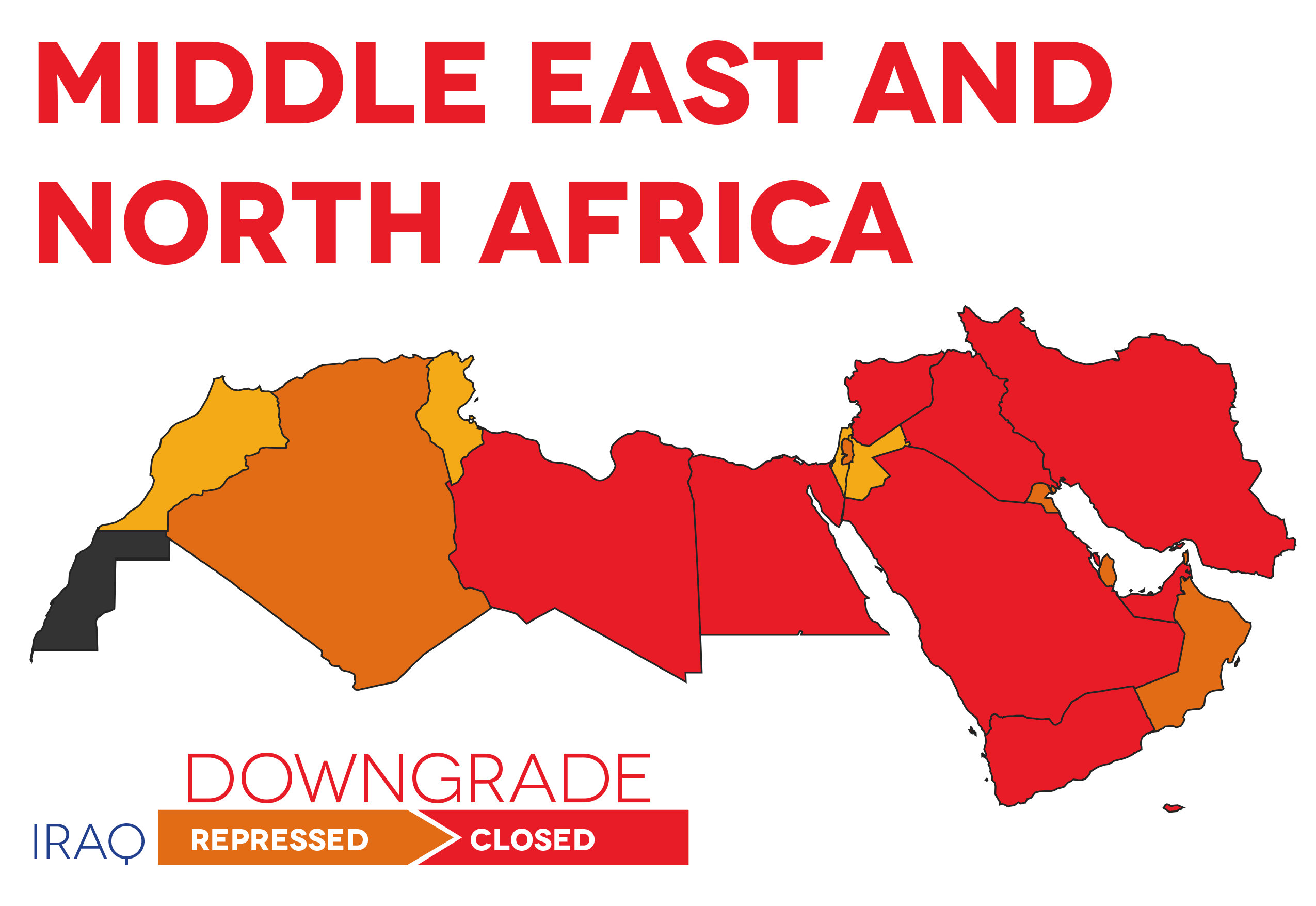

The latest CIVICUS Monitor ratings rate civic space as closed in nine countries, with five countries rated as repressed and five as obstructed. Most ratings are unchanged, apart from a notable decline in Iraq, which is downgraded from repressed to closed. This comes after a popular protest movement began in October 2019 that has seen a heavy-handed response with an extensive crackdown on the freedom of expression and many human rights violations, which continue to be documented.

Civic Space Restrictions

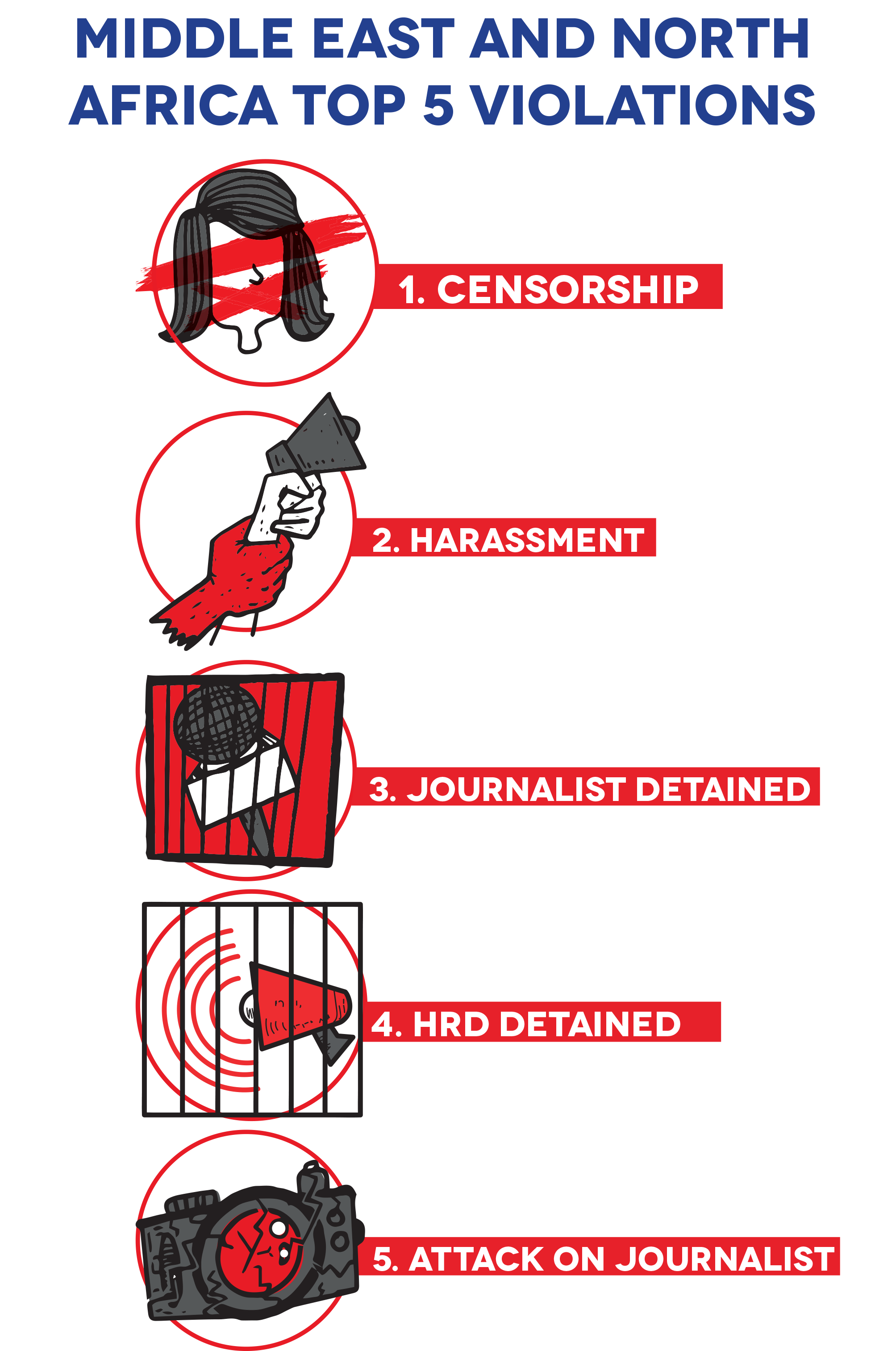

The five most reported violations in MENA during the reporting period were censorship, harassment, detention of journalists, detention of human rights defenders and attacks on journalists. Indicating that civic space challenges remain entrenched, most of these are unchanged from the five most reported violations documented in 2019, with the only variation being that attacks on journalists replaces intimidation in this latest analysis.

Censorship

Censorship retains its position as the most highly recorded violation in the MENA region, having been documented in 14 out of 19 countries.

Censorship took various forms, including the blocking of websites, as seen in Palestine when a court ordered internet service providers to block 59 websites. In Oman, the Omani Feminists Twitter account was suspended and censorship was widespread at the 2020 Muscat Book Fair, with many books by Omani writers seized and banned from display. In Morocco, the authorities enacted laws to censor and restrict expression on social networks. The suspension and closure of media outlets was another tactic, as seen in Iraq when the Communications and Media Commission ordered several TV and radio stations to be shut down and suspended the activities of the Reuters agency. In Egypt, the authorities withdrew the accreditation of a journalist while warning another over reporting in ‘bad faith’. Separately, the Egyptian Supreme Council for Media sent a warning letter to 16 news websites and social network accounts concerning posts about publishing false COVID-19 news which included a directive to ban the publishing of any information other than the Ministry of Health’s official data. In Jordan, civil society groups expressed concern that new restrictions imposed by the government to curb the spread of COVID 19 would essentially limit people’s freedom to share information or criticise the government’s handling of the pandemic.

Harassment

Harassment was documented in 11 countries. The authorities in Iran detained and summoned civil society members, journalists and members of the public who took to social media to criticise the government’s management of the COVID-19 outbreak. In Lebanon, dozens of people and activists were summoned for interrogation for their participation in the popular uprising, and also in relation to free speech charges, including insult and defamation. Harassment, as reported in Libya, also took the form of organised and systematic scrutiny and searching of personal devices by security forces, targeted towards activists, lawyers, human rights defenders, media professionals and bloggers. In Egypt, the authorities raided the homes of activists’ families to summon them for interrogation and kept them in detention. Similarly, in the UAE, state security apparatus targeted the relatives of several human rights defenders by revoking their citizenship, refusing to renew their identity documents and issuing travel bans. Judicial harassment has also often been used to punish and limit dissent, as seen in Iran in the case of human rights defender Atena Daemi, who was denied release from prison in June 2020 despite having completed a five-year term, after the authorities manoeuvred to reopen other lawsuits against her. In Yemen, some journalists were subjected to travel bans.

Journalists Detained

The detention of journalists was often used to suppress dissent across the region, as documented in nine countries.

In Egypt, security forces continued the systematic detention of journalists, as the authorities used the COVID-19 pandemic as a pretext to further restrict expression. Similarly, in Tunisia, bloggers were detained in relation to social media posts critical of the government’s response to the pandemic, while in Jordan, the authorities detained Salim Akash, a Jordan-based Bangladeshi journalist, over his coverage on the impact of lockdown measures on Bangladeshi migrant workers in Jordan. In Oman, journalists were arrested and detained for posting on social media, and in Iraq, journalists were targeted and arrested while covering the ongoing popular protest movement. In Yemen, violations were carried out by various parties in the conflict, including arrests of journalists such as Moufid Ahmed Al-Ghailani and Radwan Al-Hashed, and the sentencing of four others to death. In Palestine, journalists faced arrests from both Israeli and Palestinian forces for covering issues about the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

COUNTRIES OF CONCERN: LEBANON AND IRAQ

With the protest movements that began in October 2019 in Iraq and Lebanon continuing throughout 2020, the authorities, particularly security forces, responded by intensifying their crackdown on the rights of protesters, activists and journalists.

In Lebanon, a total of 4,338 collective actions took place as part of a nationwide anti-government protest movement. The authorities mounted a violent response to the protests which saw increased repression of civilian protesters and activists. Despite the huge August 2020 Beirut port explosion, which left in its wake a trail of destruction, a resilient civil society has defied all odds to continue its collective actions to call for governmental accountability and social justice, amid continued use of lethal and excessive force.

In Iraq, since 1 October 2019, a popular protest movement has been underway with protesters demanding better services and an end to widespread unemployment and corruption. Many human rights violations continue to be documented, the severity and scale of which indicate a drastic decline in civic space. During the past year, the CIVICUS Monitor has reported an extensive crackdown on the freedom of expression and the continued use of lethal force by the authorities and armed militia resulting in deaths and injuries of protesters on a massive scale, along with repeated attacks, kidnappings and assassinations of activists and journalists, mass arrests and detentions of protesters, activists and journalists, and internet shutdowns aimed at thwarting the protest movement.

WOMEN: Indomitable defenders of civic space in MENA

Across MENA, our analysis shows that women continue to play a major role in championing civic space and human rights more broadly. At the same time, women continue to be targeted because of their peaceful human rights work.

In Lebanon, women have been at the forefront of the popular uprising. Women’s rights and feminist organisations have played a key role in the protests through organising and mobilising people and organising specific women’s protests. In Iraq as well, thousands of women have participated in the popular protest movement. At the same time, in Saudi Arabia, the continued detention of women human rights defenders who advocated for the very limited extension of rights now enjoyed by Saudi women shows a stark contrast between the authorities’ public pronouncements on women’s rights and their appalling treatment of those who protect and promote them.

CIVICUS Monitor reports continue to illustrate the important role and remarkable resilience of women human rights defenders in standing up for civic space and the rights of women across MENA.

Positive Developments

Despite a difficult picture, there were some positive civic space developments during the year. In Bahrain, Nabeel Rajab’s conditional release from prison came after years of sustained civil society advocacy. Rajab was released alongside other prisoners of conscience, but others such as Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja remain in prison. In Iran, woman human rights defender Narges Mohammadi’s 16-year sentence for advocating against the death penalty was commuted in October 2020, enabling her release from prison. In Tunisia, the appeals court upheld the decisions of previous courts and rejected the government’s longstanding bid to shut down the LGBTQI+ rights group Shams. In Kuwait, 13 human rights defenders were acquitted of charges related to their work advocating for the rights of the excluded Bedoon community, after they were arrested and detained in July 2019.

Regional similarities and differences

Across the five regions covered by our analysis, we see common trends, but also some regional differences. For instance, in the Americas, intimidation and harassment are the most commonly reported violations. In Asia and the Pacific, the most common documented tactic is restrictive legislation. Detention of protesters tops the list in Europe and Central Asia. In MENA, the most frequently reported trend is censorship. In Africa, the detention of journalists is the most common civic space violation.