Asia - Pacific

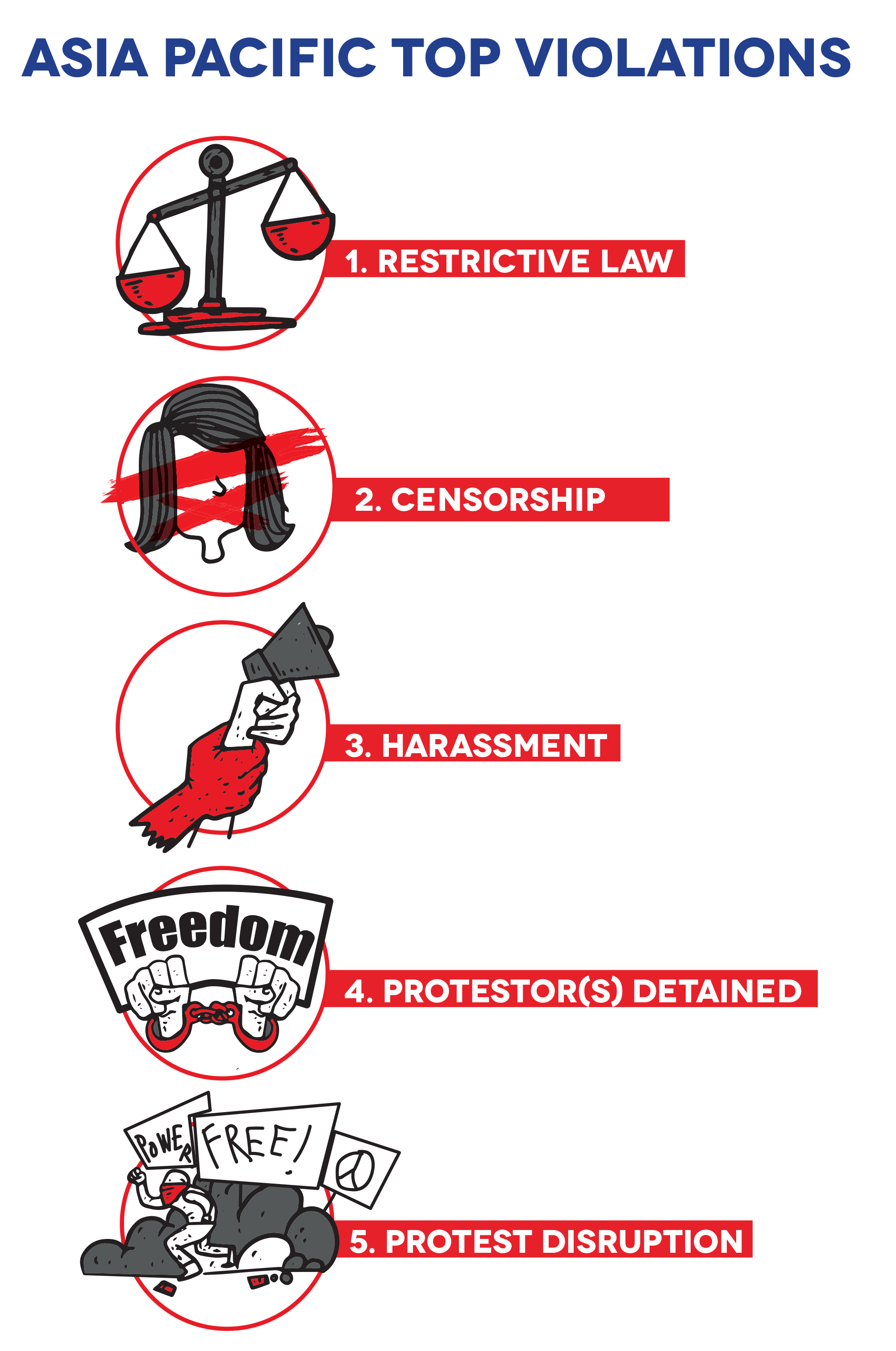

Restrictions and attacks against civic freedoms continued to occur across Asia and the Pacific in 2020, including in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the most widespread violations documented were the use of restrictive laws to criminalise and prosecute human rights defenders, journalists and critics. There have been attempts by numerous governments to stifle dissent by censoring reports of state abuses, including in relation to their handling of the pandemic. Other rampant violations include harassment against activists, the disruption of protests and detention of protesters.

Ratings Overview

Of 25 Asian countries, four – China, Laos, North Korea and Vietnam – are rated as closed, nine as repressed and nine as obstructed. Civic space in Japan and South Korea is rated as narrowed, with Taiwan the only country rated as open. In the Pacific, the story is more positive: eight countries are rated as open while three are rated as narrowed, including Australia, which was downgraded in 2019. Fiji, Nauru and Papua New Guinea remain in the obstructed category.

This year, the Philippines has been downgraded owing to its decline in fundamental freedoms. An ongoing attack on media freedom escalated when ABS-CBN – the largest media network – was forced off air, depriving people of critical information during the COVID-19 pandemic. The conviction of prominent journalist Maria Ressa in June 2020 for ‘cyberlibel’ has had a chilling effect among journalists. Senator Leila De Lima, a prominent critic of President Rodrigo Duterte, has spent more than three years in detention on fabricated charges. Human rights defenders, such as Zara Alvarez and Randall Echanis, have been attacked and killed with impunity. Others, like human rights defender Teresita Naul, have been criminalised or subjected to ‘red-tagging’ – a practice of labelling individuals and groups as communists or terrorists – as a result of their work. A new anti-terrorism law passed in July 2020 includes a broad definition of terrorism that gives law enforcers exhaustive powers and provides few safeguards against abuse, leaving it open to exploitation by those seeking to silence dissent.

Civic Space Restrictions

In the Asia-Pacific region, the civic space violations most frequently documented by the CIVICUS Monitor in this period were restrictive laws, censorship, harassment, detention of protesters and protest disruption.

Restrictive laws used to stifle dissent

The use of restrictive laws against human rights defenders, journalists and critics, the most common civic space violation documented in Asia and the Pacific during the reporting period, occurred in at least 26 countries. Legislation most often used included laws related to national security, public order and criminal defamation. In at least 16 countries, human rights defenders were prosecuted.

In China’s closed civic space, scores of activists, lawyers and critics were detained on charges based on vague and overly broad legislation, from ‘subverting state power’ to ‘picking quarrels and provoking trouble’. China also escalated its repression in Hong Kong. In June 2020, a new draconian national security law was imposed in the territory that is being used to silence free speech, including targeting overseas activism. The authorities have continued to arrest and prosecute pro-democracy activists.

In Vietnam, scores of activists were arrested or jailed after summary trials under an array of restrictive laws for ‘abusing democratic freedoms’ and ‘anti-state propaganda’, including bloggers and Facebook users. In Cambodia, Prime Minister Hun Sen’s government has used ‘incitement’ laws to prosecute dozens of critics, including land and environmental human rights defenders, trade unionists, journalists, youth activists and musicians, in an escalation of repression. Amid the pandemic, Cambodia passed an emergency law giving the executive sweeping powers. Indonesia has continued to criminalise West Papuan activists for ‘rebellion’.

Criminal defamation laws often continue to be deployed in a number of countries to silence dissent. In Bangladesh, the Digital Security Act is the weapon of choice used by the authorities to pursue critics, including those critical of its handling of the pandemic. Media workers, activists, academics and students have been targeted, including prominent journalist Shafiqul Islam Kajol, who was charged in May 2020 after he was forcibly disappeared for 53 days. In Malaysia, the Communications and Multimedia Act has been used to prosecute online criticism of religion and the monarchy and for spreading misinformation on COVID-19, while in Myanmar people criticising the military, such as members of the Peacock Generation poetry troupe, have been convicted and imprisoned for defamation under the Telecommunication Law and penal code. In India, Pakistan, Thailand and Singapore as well, restrictive laws have regularly been used against civil society.

In the Pacific, restrictive laws were passed or used in at least seven countries. Australia is using its Intelligence Services Act to prosecute a whistleblower for disclosing the bugging of Timor-Leste government buildings in 2004. In Fiji the Public Order (Amendment) Act 2014 has been used to silence and prosecute critics, including trade union leader Felix Anthony.

Censorship of journalists and critics

Censorship of media outlets, journalists, civil society and critics was another serious violation documented in the region, occurring in at least 24 countries. China, which has an extensive censorship regime, deployed it to block foreign websites, cover up its persecution in Xinjiang and Tibet and target its critics abroad. The authorities also censored articles and social media posts about COVID-19 by journalists, doctors, activists, academics and critics.

In Bangladesh, the authorities continued to block numerous news sites critical of the government, including investigative journalism website Netra News. In Pakistan, the authorities have attempted to silence media outlets such as The Dawn Media Group and The Jang Media Group for their critical reporting, and to block online content. In Thailand, the authorities used an emergency decree passed to handle the pandemic to instead target media outlets covering pro-democracy protests in October 2020.

Censorship was documented in at least six countries in the Pacific. In August 2020, Fiji Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama ordered the Fiji Broadcasting Corporation to stop airing a debate. In Vanuatu, media outlets were not allowed to publish articles on COVID-19 without government authorisation.

Harassment of activists and journalists

There have been reports of online and offline harassment of activists and journalists in at least 22 countries. In China, the government continues to intimidate and harass human rights defenders with raids on their homes and offices and subject their family members to police surveillance. The Communist Party has also used COVID-19 as a pretext to expand its surveillance regime. Vietnam’s one-party regime continued to harass those who criticised it, including activists and bloggers. Many were kept under surveillance or detained for months without access to legal counsel and subjected to abusive interrogations.

In Indonesia, activists and critics, in particular those speaking up on the severe violations in West Papua, were subjected to digital attacks, smear campaigns and surveillance. The authorities in Malaysia have harassed activists and journalists, as well as news outlets Al Jazeera and Malaysiakini.com, for their critical reporting. Singapore has deployed its Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act, a sweeping piece of legislation on misinformation, to harass online critics.

In Sri Lanka, human rights lawyers and journalists faced harassment and arrests ahead of the August 2020 elections. Activists and families of survivors seeking accountability for crimes committed during the civil war have been intimidated and subject to surveillance. Women journalists in Pakistan faced a gender based cyber-harassment campaign against them by government officials and supporters while Pashtun activists continued to be targeted. In the Maldives, the government forced a leading CSO to close and seized its funds while in Bangladesh journalists have faced harassment and physical attacks by activists from the ruling Awami League party with impunity. Journalists have also been attacked for their reporting in Afghanistan, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

Crackdown on protests

Protesters continued to stand up for their rights throughout the region, despite risks and restrictions. In 20 countries, protests were disrupted, and in 15 of those countries, protesters were arrested. In nearly all cases where security forces used excessive force against protesters, no one was held accountable for the violence.

In Hong Kong, pro-democracy protest leaders continued to be arrested and charged under the Public Order Ordinance. Activists were also targeted for taking part in the Tiananmen Square massacre anniversary vigil, including activist Joshua Wong. In Myanmar, dozens of protesters have been charged under the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law for various protests against land grabs, development projects and the internet shutdown in Rakhine and Chin States.

In Indonesia, hundreds were arrested in October 2020 for mass protests against an omnibus law that will erode workers’ protections and remove environmental safeguards, while in Thailand the authorities escalated their crackdown on youth-led peaceful democracy protests with at least 90 people arrested in October 2020. Thai authorities also physically blocked access to protest sites and shut down transportation networks. In several countries, including Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Thailand, police used excessive force against peaceful protesters.

In the Pacific, even as climate change manifested in fires and floods, environmental and climate action protesters in Australia were vilified and arrested.

Country of concern: India

Civic space in India, which was downgraded in 2019 to repressed, continues to regress. The government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has continued its persecution of human rights defenders, student leaders, journalists and those involved in protests against the discriminatory Citizenship (Amendment) Act. A variety of restrictive laws, including national security and counter-terrorism legislation such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, have been used to detain activists such as Sudha Bharadwaj for prolonged periods. Many who are jailed have been placed at risk of contracting COVID-19 in overcrowded and unsanitary prisons. The Foreign Contribution Regulation Act has been used to target outspoken groups while the authorities continue to impose harsh and discriminatory restrictions in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir

Positive Developments

In a challenging year for fundamental freedoms, the CIVICUS Monitor documented a number of positive civic space developments, which are testament to the commitment of those who have fought for them. In Afghanistan, in January 2020, the authorities made a public commitment to establish a protection mechanism for human rights defenders, while Papua New Guinea passed a whistleblowers law in February 2020.

In Thailand, courts dismissed defamation cases brought against human rights defenders for exposing labour rights violations. In Indonesia, a court ruled in June 2020 that the government’s decision to impose an internet blackout during weeks of protests in the West Papua region in 2019 violated the law. Human rights groups played a key role in bringing Myanmar before the International Court of Justice for violations of the Genocide Convention. Taiwan hosted one of the few Pride marches around the world in June 2020, as the island’s LGBTQI+ community took to the streets, visibly asserting their rights.

Regional similarities and differences

Across the five regions covered by our analysis, we see common trends, but also some regional differences. For instance, in the Americas, intimidation and harassment are the most commonly reported violations. In Asia and the Pacific, the most common documented tactic is restrictive legislation. Detention of protesters tops the list in Europe and Central Asia. In MENA, the most frequently reported trend is censorship. In Africa, the detention of journalists is the most common civic space violation.